Napoleon was the kind of guy who didn’t know when the party was over. Following his disastrous defeat in Russia in 1812 (chronicled in Episodes 10-12 of this podcast) and yet another war in Europe, Napoleon’s enemies invaded France and forced him off the throne in the spring of 1814. Bonaparte was given the paltry consolation prize of the island of Elba, which proved stifling, and he had little hope that his enemies, particularly Britain, Austria and the restored monarchy of France, would abide by their word not to bother him. Within nine months of exile Napoleon had returned to France for another bid at power—an adventure that would ultimately lead to the Battle of Waterloo. Was Napoleon just desperate, stroking his ego, or was there really a chance that his return could have worked?

In this episode, the first in season three, Dr. Sean Munger delves into the back-story of Napoleon’s audacious comeback, including the circumstances of how and why he ended up on Elba and why he thought he had to leave. We’ll explore the shifting and contradictory motives of the allies, why Napoleon suddenly found himself broke, how and why Louis XVIII, the new King of France, totally deluded himself, and the currents and turmoils within France that ultimately made the success of Napoleon’s comeback a definite long-shot. This is the first in a projected three-part series that will chronicle Napoleon’s final turn on the world stage, ultimately ending with the climactic Battle of Waterloo—one of the most dramatic moments of the Second Decade.

Additional Materials About This Episode

[Above] One of the most famous pictures ever painted of Napoleon, Paul Delaroche’s painting depicts Bonaparte just after he reluctantly signed the instrument of abdication forced upon him by the Allies on April 6, 1814. Six days later he would try unsuccessfully to end his own life.

[Above] Rested from his suicide attempt but still weak and surly, Napoleon bids farewell to his Imperial Guard in Paris as he departs the capital en route to (supposed) permanent exile on the island of Elba.

[Above] King Louis XVIII, the restored Bourbon monarch of France. The Allies were not entirely enthusiastic about putting Louis, the younger brother of the executed Louis XVI, on the French throne in Napoleon’s place in 1814, but there were few alternatives, and none that were consistent with the other powers’ narrative that the French Revolution of 1789 had been an unnatural affront to the divine right of kings. That narrative was also why the Allies could not simply execute Napoleon or put him on trial—as might have been done in the 20th century—and related to the idea that monarchs, however unsatisfactory, were generally regarded as being above the law.

[Above] The Empress Josephine as she appeared in her final years, between the divorce from Napoleon in 1810 and her death in the spring of 1814. Napoleon demanded an heir which she was incapable of providing, but he still loved her to the end and found very little happiness with his second wife, Marie-Louise of Austria. Josephine’s name was the last word Napoleon spoke before his death in May 1821.

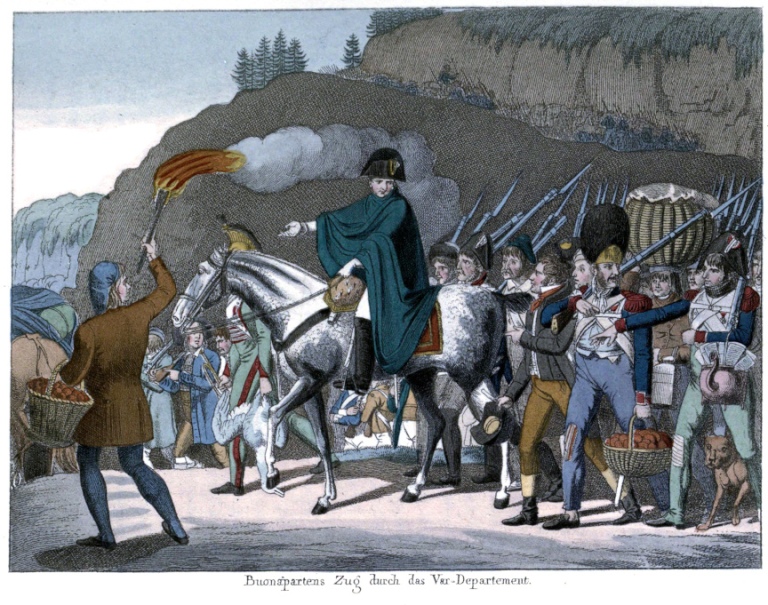

[Above] A contemporary German print of Napoleon marching through the Alps on his way from Golfe-Juan toward Paris in March 1815. Through charisma, luck, audacity and the wise policy of not tempting areas with heavy pro-royalist sentiments, Napoleon managed to avoid major confrontation with Bourbon forces on his march through France. Most of the soldiers sent out to arrest him ended up joining him, swelling the armies that would ultimately take the field at Waterloo. Note all the food and supplies the soldiers are carrying.

[Above] Modern France has a curious relationship with Napoleon and his legacy. While his excesses as a dictator and warmonger are never forgotten, in some quarters he is celebrated as the essence of French nationalism. Witness these monuments, with French Imperial eagles, that appear on the modern roads that correspond to Napoleon’s route on his return in 1815. The commemorative trail is known as the Route Napoleon. [Photo by Wikimedia Commons user La Treille, Creative Commons 3.0 license.]

One thought on “Episode 36: Napoleon’s Hundred Days, Part I”